In Yemen, Everyday Life Goes from Bad to Worse

April 7, 2015

Share

Today, the conflict in Yemen has pulled in the most powerful countries in the region: a military campaign led by Saudi Arabia, whispers of Iranian influence, and even the prospect of ground troops from Gulf countries.

But the problems that started the conflict were homegrown.

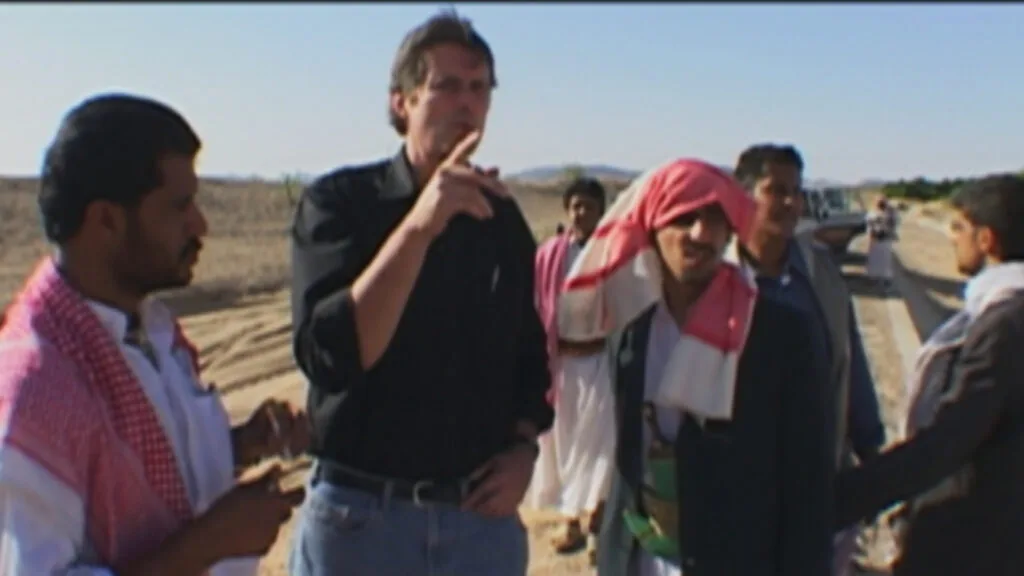

“The root of the problems are Yemeni problems,” said Ali Soufan, a former FBI counterterrorism agent and CEO of the Soufan Group, a security research firm. “They didn’t suddenly erupt.”

Yemen is one of the poorest countries in the Arab world, with more than half of the country — 54 percent — living in poverty, according to the World Bank. At the same time, it has one of the highest population growth rates in the world. It’s an oil-based economy, but the revenues don’t flow to the people. According to Transparency International, Yemen is considered one of the most corrupt countries in the world.

Two of Yemen’s greatest problems are also the most basic: food and water. Many citizens in the capital, Sanaa, get tap water only a few times each week, and access in rural areas can be even worse. Sanaa may be the first capital in the world to run out of a viable water source, according to the U.N. With access to clean water dwindling, the risk of diseases like dengue fever and cholera has also increased.

The water shortage is due in part to a dependence on growing qat, a plant that, when chewed, produces a mild high. Qat requires tons of water — more than half of what the country uses — but it’s also incredibly popular, and more lucrative for farmers than growing food. Which brings us to another problem.

Before the latest crisis, 10.6 million people — a full 41 percent of the population — were considered “food insecure,” by the World Food Program, meaning they can’t regularly obtain or afford enough to eat. The country must import most of its food.

Dwindling resources have fueled tension along sectarian fault lines, deepening the country’s political instability.

Yemen is the eighth most fragile country in the world, according to a ranking by Foreign Policy magazine. The nation of nearly 25 million was considered more unstable than Haiti, Pakistan and even ISIS-plagued Iraq.

That ranking was actually an improvement. Over the past few years, observers had regarded Yemen with guarded optimism. The Arab Spring had brought signs of promise to the Gulf nation. In Nov. 2011, after months of popular protests, longtime President Ali Abdullah Saleh resigned, handing power to his vice president, Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, in exchange for immunity. Hadi was elected president a little over a year later, and began holding negotiations to draw up a new constitution.

But the new government was weak. And after decades under Saleh, local grievances quickly festered. In the north, rebels from the Houthi movement, who follow an offshoot of Shiite Islam, wanted justice after years of violent repression. Saleh had also plundered the oil-rich south, and some Sunni tribes there demanded secession. Some of the Sunni tribes also remained allied with Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). The Yemen-based Al Qaeda franchise has waged attacks overseas and against the Yemeni government. Now, it also battles the Houthis, who control the capital.

Today’s conflict has only made Yemen’s local problems worse. Airstrikes by Saudi Arabia — which are supported by the U.S. — have destroyed homes, hospitals, schools and infrastructure, according to Zeid Ra’ad al Hussein, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights. Hundreds of people have fled their homes and more than 500 people have been killed, the U.N. said, including an estimated 19 in a strike on a camp for displaced people in northern Yemen.

“The killing of so many innocent civilians is simply unacceptable,” al Hussein said.

In the meantime, Yemen’s longterm concerns — the poverty, the water shortages, the food crisis — have all been pushed aside, even as the crisis deepens. Last week, Saudi forces began a naval blockade of Yemeni ports to keep weapons from getting into Houthi hands, which will also make it difficult for critical food shipments to get through.

Related Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Related Stories

Related Stories

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.