Study Offers Disturbing False Confession Insights

August 12, 2011

Share

It’s remarkably easy to confess to something you didn’t do, and more people are inclined to do so than you might think.

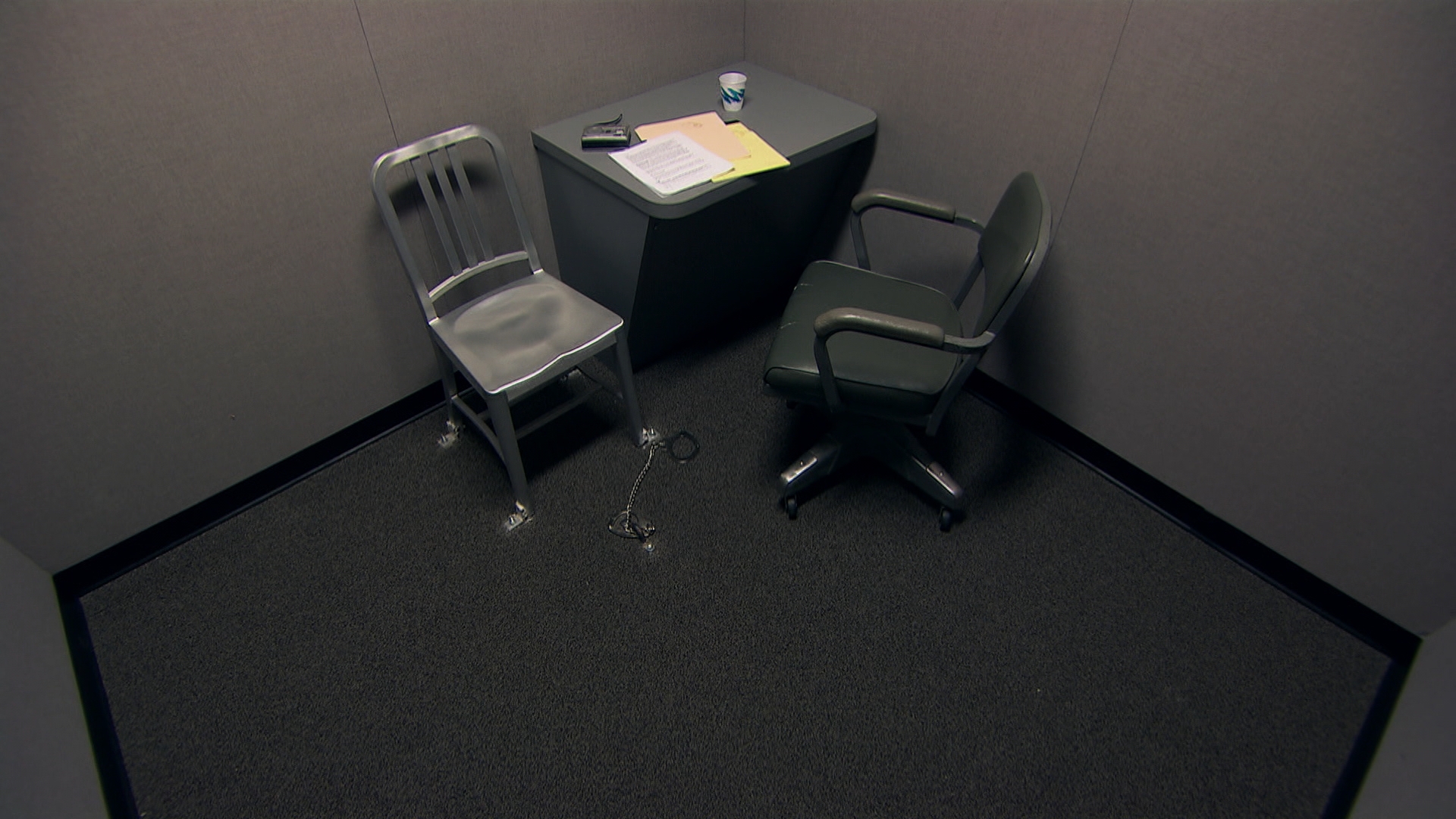

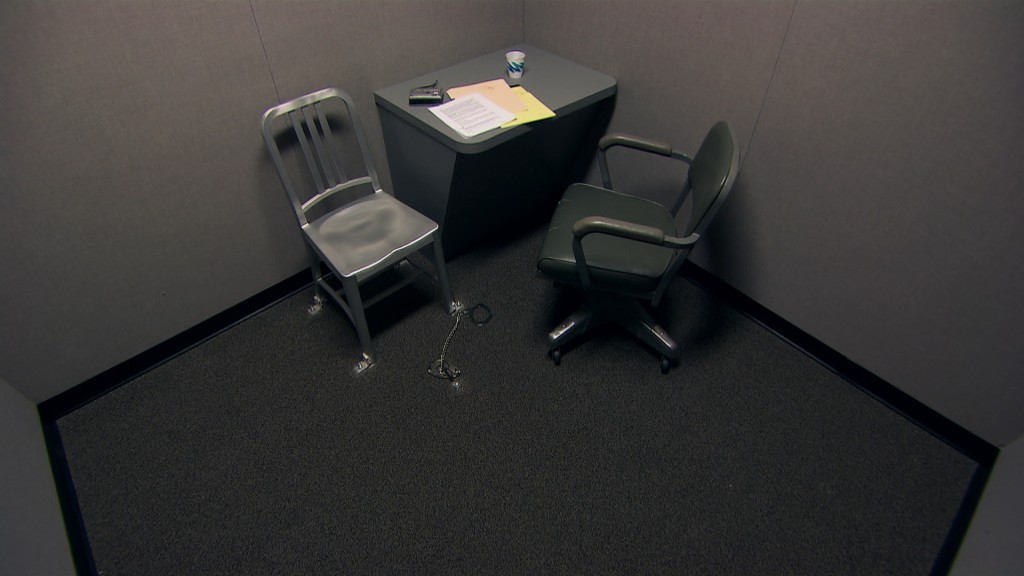

This according to new research on false confessions, smartly analyzed in the latest issue of The Economist. One particularly telling study [PDF] was conducted by renown false confession researcher Saul Kassin and Jennifer Perillo out of the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The researchers took a common interrogation technique known as the Reid Technique (here’s a great Robert Kolker piece in New York magazine on its history and controversy) and applied them to student volunteers who were told they were being tested on reaction times. The students were warned about a kink in the computer system:

The volunteers were informed that the ALT key was faulty, and that if it was pressed the computer would crash and all the experimental data would be lost. The experimenter watched the proceedings from across the table. In fact, the computer was set up to crash regardless, about a minute into the test. When this happened the experimenter asked each participant if he had pressed the illicit key, acted as if he was upset when it was “discovered” that the data had disappeared, and requested that the participant sign a confession. Only one person actually did hit the ALT key by mistake, but a quarter of the innocent participants were so disarmed by the shock of the accusation that they confessed to something they had not done.

Then Kassin and Perillo added a twist that mimics the real-life role of a witness or informant:

A second computer-crash test conducted by Dr. Kassin and Dr. Perillo used this technique. Another person in the room beside the experimenter said he saw the participant hitting the ALT key. In this case the confession rate jumped to 80 percent of innocent participants.

And what if the accused thinks there’s DNA or other solid evidence that can exonerate them? Kassin and Perillo found disturbing results in these cases as well:

Two participants, one of whom was again in cahoots with the investigator, sat in the same room and were asked to complete what appeared to be an academic test. Halfway through, the investigator accused them of helping each other and cited the university’s honour code against cheating. The investigator went on to bluff that there was a video camera in the room, though the recording, with its definitive proof one way or the other, would not be accessible until later. In the real world, this might be like a detective telling a suspect that DNA or fingerprint evidence had been found but not yet analysed (in Britain as well as America, if such a statement were actually true, police would be permitted to say it, though in the case of the experiment it was a lie). Presumably, the innocent participants knew such a tape would exonerate them. Even so, half still confessed.

So what can happen when the stakes are much higher than data being lost on a computer? The Economist soberly points out that a fourth of the 271 people exonerated by the Innocence Project with DNA evidence confessed or pleaded guilty to crimes they did not commit. In addition, our 2010 investigation into the “Norfolk Four” offers up a particularly jaw-dropping case study of false confessions gone terribly awry.

Related Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Related Stories

Related Stories

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.