The Long March of Newt Gingrich: Part Four

December 20, 2011

Share

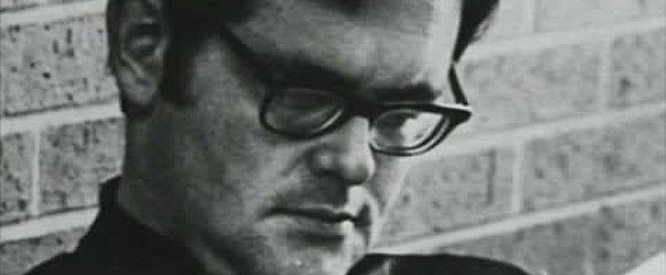

“Gingrich learned that the easiest way for someone to get access to the news media was to be controversial, and, in particular, to be quotable. And so from the very beginning of his stay in Washington, he was quotably controversial.”

— Marc Rosenberg, former Gingrich aide

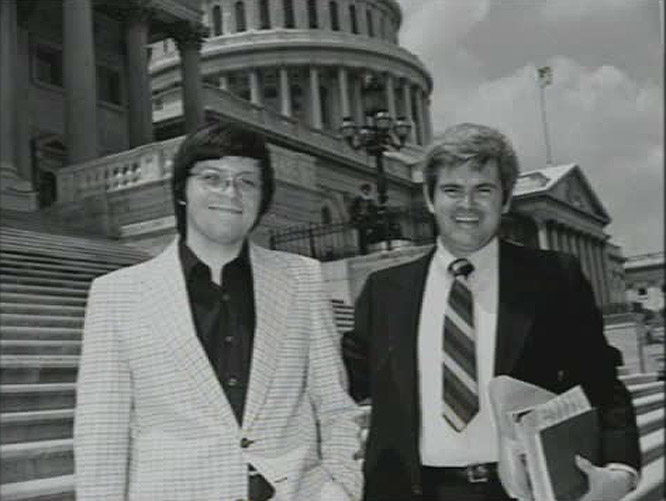

Newt arrived in Congress with two dreams: become speaker of the House and build a Republican majority.

To defeat the Democrats, Newt believed Republicans must destroy their mindset as a complacent minority, willing to compromise. In Washington, he founded the Conservative Opportunity Society, recruiting other conservative House Republicans, like Rep. Vin Weber of Minnesota. “We started talking through who we would want to try to bring into a room of people that could challenge the minority mind-set within our own party while challenging the Democrats at the same time,” Weber recalled:

He had a construct and we really developed it. We needed to develop as a party – wedge issues and magnet issues. It’s a fairly simple notion with wedge issues, or ideas that really separated the Democratic majority from the public, issues where they were plainly wrong and the public did not support them, but they were, for a variety of reasons, not paying a political price. In those cases our assignment was to find ways of making clear the differences. …

The magnet issues really relate to this concept of a Conservative Opportunity Society — always understanding that you can’t just win by being negative. Ultimately there has to be a positive set of issues that attract people to the Republican Party, issues for which they feel confident voting for.

Gingrich seized on new media, like C-Span, to attack the enemy and recruit his own political army. On May 15, 1984, before an empty House chamber, he delivered a long list of accusations against House Democrats for being soft on communism, a broadside that then-Speaker Tip O’Neill (D-Mass.) described as “the lowest thing that I’ve ever seen in my 32 years in Congress!” For several hours, Gingrich and O’Neill engaged in what an observer described as “an old-fashioned partisan intellectual and ideological shoot-out.”

In 1987, Gingrich mounted a two-year battle that brought down Speaker Jim Wright (D-Texas), accusing him of ethical misconduct. It was a turning point for his reputation. “Up to that point, he was regarded as an interesting political figure, somebody that was very good for a quote, but not somebody who was perhaps going to be in the power structure,” explained conservative activist Paul Weyrich. “When he took on Jim Wright and he won, he was regarded very seriously from that moment on.”

Bonus: “Good Newt, Bad Newt” — Peter J. Boyer’s July 1989 Vanity Fair profile, written during Newt’s campaign against Jim Wright. And in The New York Times, Sheryl Gay Stolberg writes about how the Conservative Opportunity Society grew out of a conversation between Newt and former president Richard Nixon.

Produced by Steve Talbot, The Long March of Newt Gingrich was a co-production with the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Related Documentaries

Latest Documentaries

Related Stories

Related Stories

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.