Massacre in El Salvador

November 9, 2021

27m

FRONTLINE, Retro Report and ProPublica examine the ongoing fight for justice for the horrific 1981 attack on the village of El Mozote and surrounding areas

Massacre in El Salvador

November 9, 2021

27m

Share

Massacre in El Salvador examines the horrors of what happened when U.S.-trained and -equipped Salvadoran soldiers killed some 1,000 civilians, many of them children.

FRONTLINE, Retro Report and ProPublica’s investigation follows the ongoing fight for justice for the horrific 1981 attack on the village of El Mozote and surrounding areas, and how today the case against high-ranking military officials is faltering under Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele.

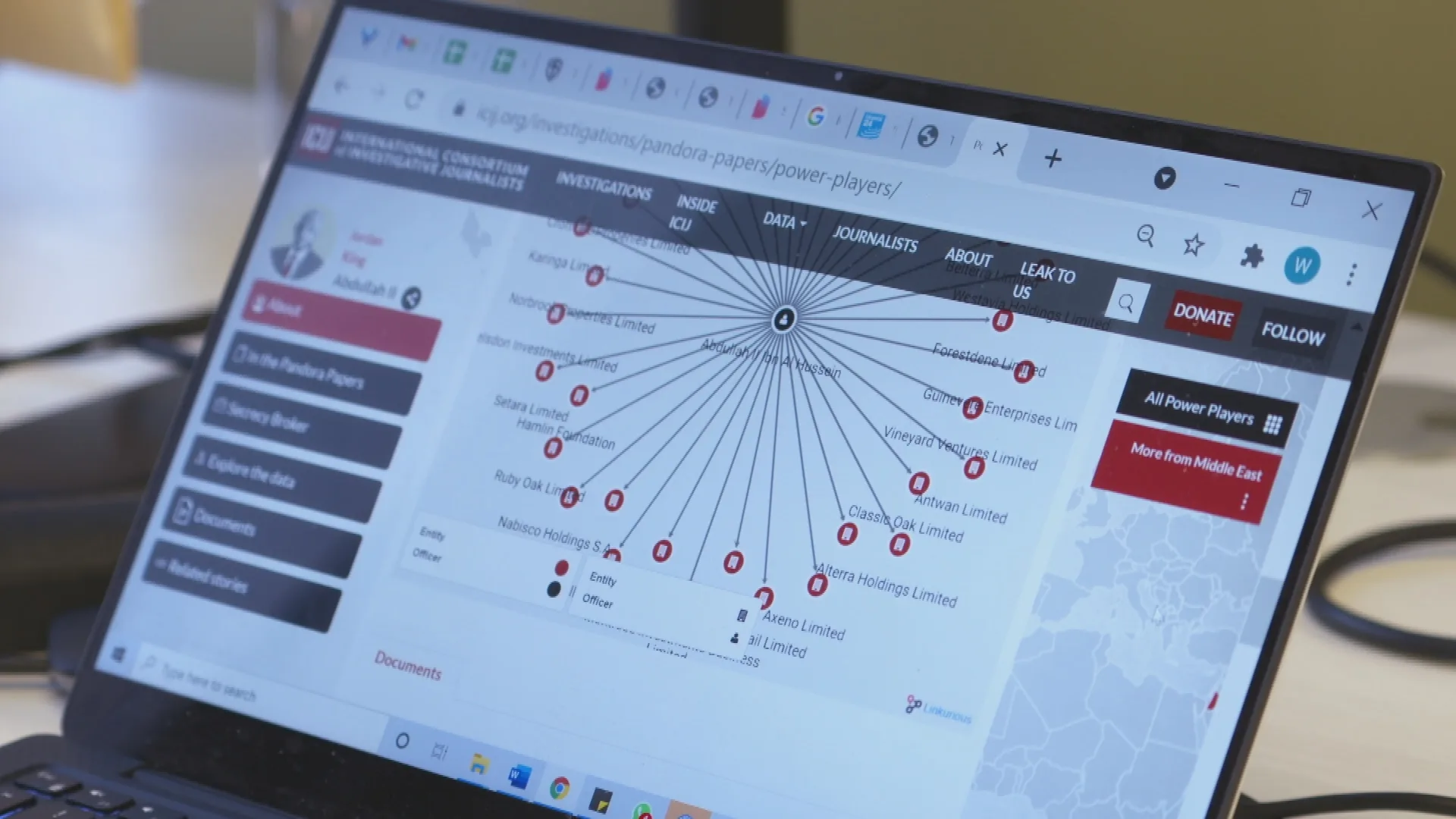

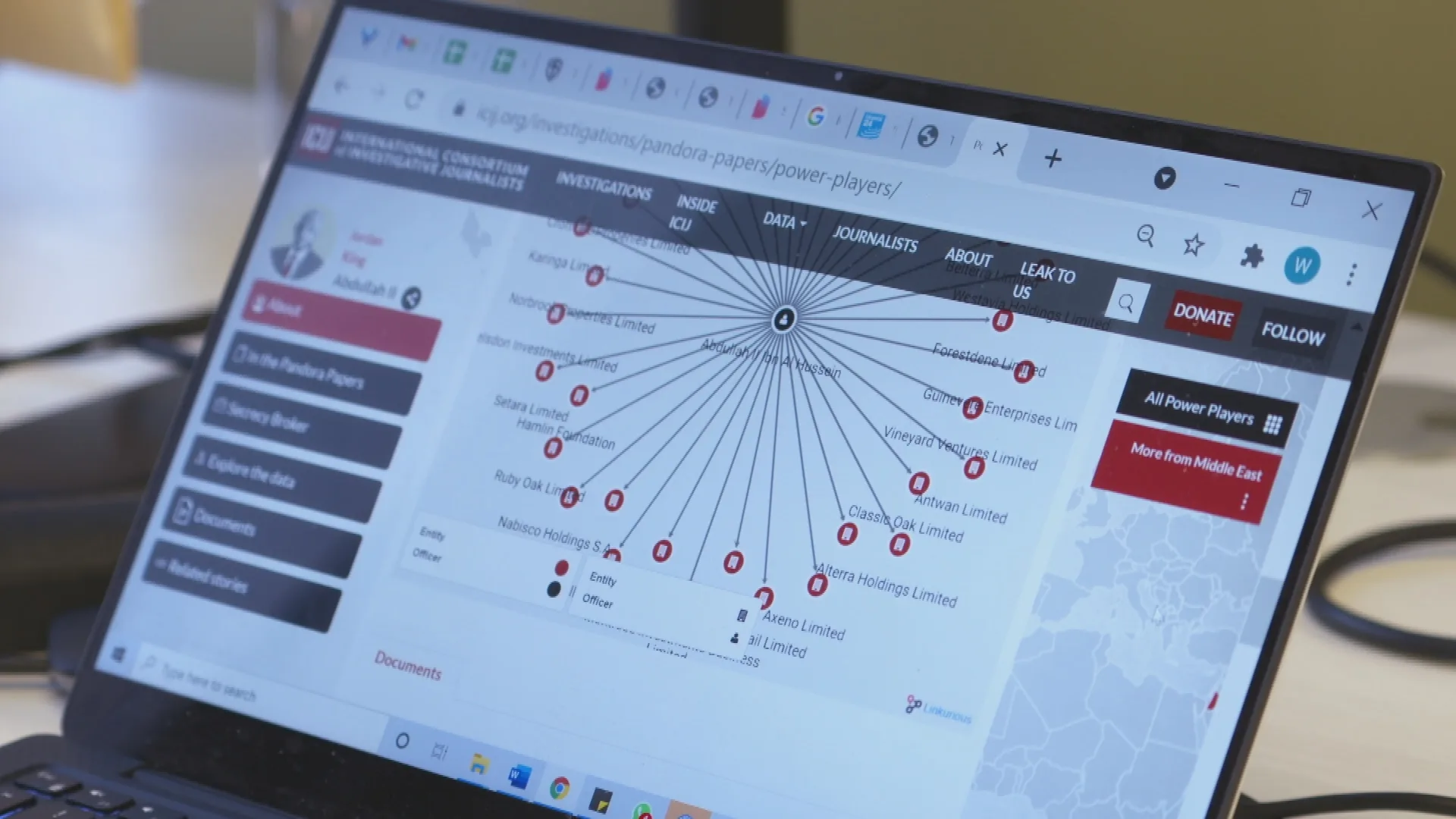

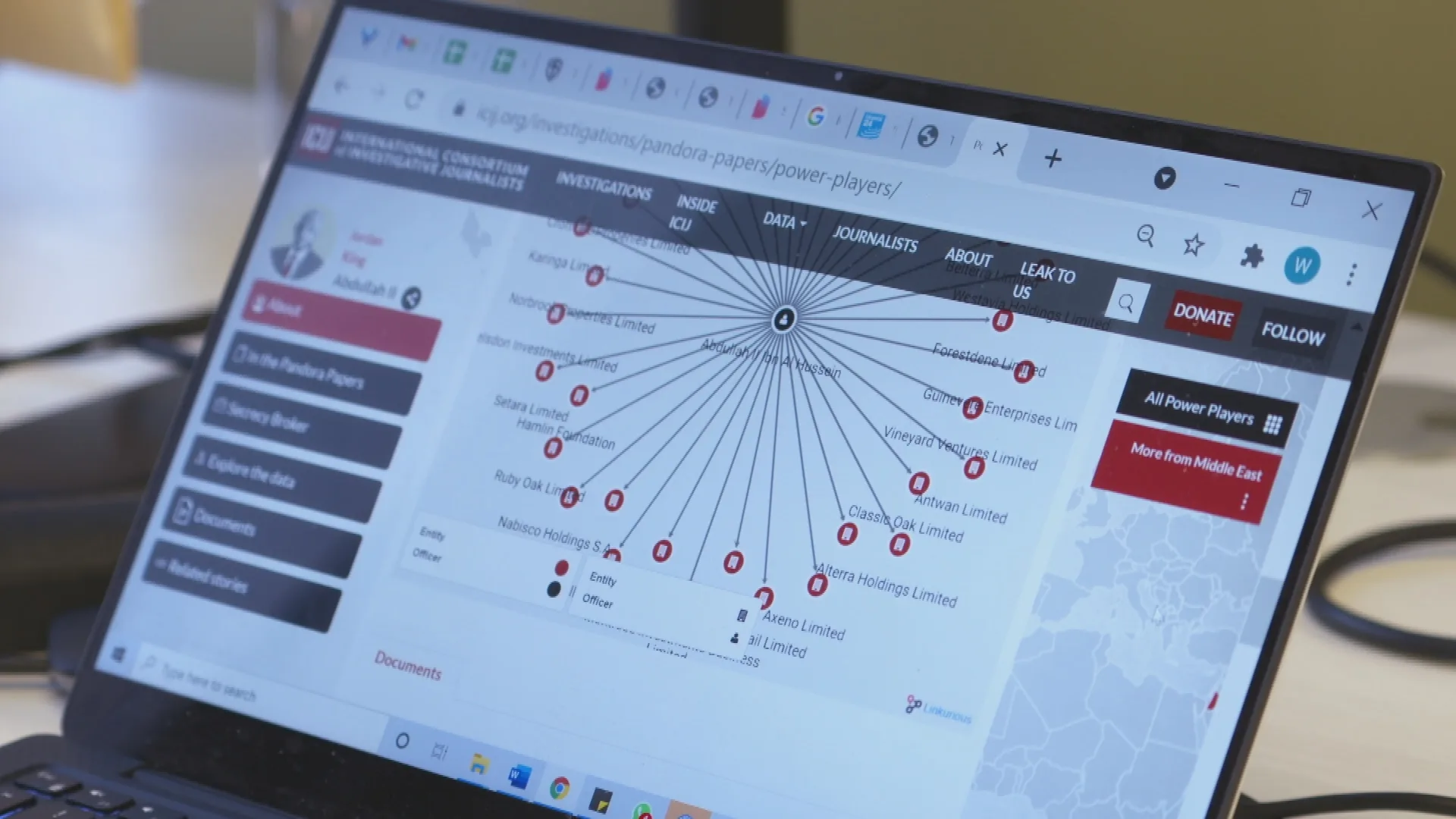

Also airing in FRONTLINE’s two-part Nov. 9 hour: Pandora Papers, an examination of secret finance overseas and in the U.S., in collaboration with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

Support provided by:

Learn More

Most Watched

The FRONTLINE Newsletter

The High Price of Doing Journalism in El Salvador

Pandora Papers

Related Stories

The High Price of Doing Journalism in El Salvador

Related Stories

The High Price of Doing Journalism in El Salvador

This program contains graphic imagery. Viewer discretion is advised.

AMADEO MARTINEZ SANCHEZ:

[Speaking Spanish] Around 7 or 8 a.m., the helicopters started flying around. Around 9 a.m. we heard them start to kill the people of El Mozote. Suddenly we saw some soldiers coming down the hill. First they took two young women toward the river. They raped them and the girls screamed. Then they came to take the children out, pulling them by the arm, almost dragging them. One of the kids cried out, “My mom is left behind!” They sent two soldiers to see and shortly after—pum! We heard gunshots.

And I saw writing on the wall in the blood of those who were murdered. “One dead child, one less guerrilla.”

PRESIDENT RONALD REAGAN:

Very simply, guerrillas are attempting to impose a Marxist-Leninist dictatorship on the people of El Salvador.

NARRATOR:

The story of one of the worst massacres in the modern history of Latin America began in December 1981. It was in the midst of the Cold War. The United States was supporting the government of El Salvador’s fight against communist-backed rebels, known as the FMLN.

MALE VOICE:

[Speaking Spanish] Radio Venceremos. Official voice of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front.

SUSAN MEISELAS, Photojournalist:

There were a lot of risk involved. There were targeted killings of people who organized peasants, organized labor, organized within their churches.

So this is more of Mozote’s houses.

NARRATOR:

Photojournalist Susan Meiselas was covering the war when she began hearing rumors of a government attack on civilians in a remote village.

RADIO VENCEREMOS ANNOUNCER:

—[Speaking Spanish] we bring you, from the people of El Mozote, a new testimonial.

NARRATOR:

She and her colleague, foreign correspondent Raymond Bonner, who was working for The New York Times, decided to go behind rebel lines.

SUSAN MEISELAS:

I think that’s you.

NARRATOR:

With the help of FMLN fighters, they crossed into the Salvadoran mountains.

SUSAN MEISELAS:

We heard about something, but we didn’t really know. And the question was, how do we even find out? Could we even find out, or find a means of a path to trying to find out?

We were walking in a terrain that was completely unknown to us. There was no path. There was no map. But because we felt compelled, we just had to dig deeper. We had to know more.

We walked into a tiny pueblo that was completely evacuated. All the houses had been burned to the ground. You saw the remains of people. You felt like it was a ghost town. It was eerie. It was like time was frozen.

NARRATOR:

The village was called El Mozote.

RAYMOND BONNER, Fmr. correspondent, The New York Times:

I remember their bodies lying in the cornfield. It was clear this had been a scorched earth policy, if you will. They’d come through and just killed every man, woman and child they found.

SUSAN MEISELAS:

There was nothing that explained what happened except the remains. The remains couldn’t speak to us.

You remember the guy that showed us that?

NARRATOR:

They soon met a woman named Rufina—

SUSAN MEISELAS:

And that’s Rufina.

RAYMOND BONNER:

Right.

NARRATOR:

—sitting in the middle of the village, in shock.

SUSAN MEISELAS:

Rufina the next day or two spoke to us and filled in what we were seeing.

Audio interview

December 1981

RUFINA AMAYA MARQUÉZ:

[Speaking Spanish] When they took us all out and lined us up to be killed, I stayed behind, I hid, and the assassins didn’t see me. And then they killed every single woman. After they killed all the adults they started talking about how they were going to kill the children. And I saw the ropes they were making to hang the children after they were done killing the others. In the end, no one but me emerged from El Mozote.

NARRATOR:

Rufina was one of the few survivors and told the reporters of how government soldiers had laid siege to her town.

SUSAN MEISELAS:

She talked about seeing her husband pulled away, the kids screaming. She was so numb I don’t think she even shed a tear in the telling. Could we believe this woman, a peasant woman, sitting in the middle of a field, pretty much in shock herself?

NARRATOR:

After two weeks of reporting in the region, Bonner and Meiselas’s story landed on the front page of The New York Times. It detailed the massacre of over 700 people in El Mozote and surrounding villages by an elite Salvadoran military unit—the Atlacatl Battalion.

RAYMOND BONNER:

It was the most elite unit in the Salvadoran army.

MALE REPORTER:

They’ve been specially trained by the United States Green Berets, and they are undoubtedly the cream of the Salvadoran army.

RAYMOND BONNER:

It was an American-trained battalion, and equipped. All their uniforms, all their M16 rifles, the helicopters that flew them into El Mozote, all supplied by the United States.

NARRATOR:

The U.S.-backed Salvadoran government quickly denied the allegations. But inside the American Embassy they realized they had a problem.

TODD GREENTREE, Fmr. U.S. Foreign Service officer:

The news doesn’t get any bigger than this. Front page of The New York Times. Front page of The Washington Post.

NARRATOR:

At the time, Todd Greentree was a junior officer at the embassy.

TODD GREENTREE:

There was a lot going on at the time. There were death squad killings every day. We were associated with a government of which major elements were conducting state terror. And if it meant killing women and children, well, they were just the byproduct of this. So it was in that context that I received a message that there had been this massacre.

NARRATOR:

The news reports about the massacre in El Mozote were explosive. They landed just days before congressional hearings on continuing aid to El Salvador. The Reagan administration’s Cold War strategy in Central America was on the line.

TODD GREENTREE:

It was a sense of realization from the start that what’s at stake is the entire policy. That was the problem.

NARRATOR:

As worries grew, Greentree and a military attache were sent to find out what happened in El Mozote.

TODD GREENTREE:

So, we flew out in a helicopter and could see a fairly wide amount of destruction. So it was obvious there had been a military operation. We went out to a displaced persons camp where people had fled El Mozote and were gathered. That was a bit of a tricky situation, because we’re being transported by Salvadoran soldiers. It was obvious that the people in that camp were traumatized. There was no question.

I pretty much concluded that something had happened, something bad had happened.

NARRATOR:

But Greentree and his partner wanted to reach El Mozote itself, which was in dangerous rebel-held territory.

TODD GREENTREE:

We’d finally got to a point where the sergeant who was in the jeep with us just stopped and said, “That’s it, we’re not going any farther.” They were scared to death, basically. So we never reached the site.

NARRATOR:

Back at the embassy, Greentree wrote up what he had seen.

TODD GREENTREE:

I had drafted a report that basically said, “We can conclude from the evidence, from what we’ve seen, what people said, that there was a massacre.”

NARRATOR:

But that’s not the report that reached Congress days later when U.S. Assistant Secretary of State Thomas Enders went to testify.

THOMAS ENDERS:

There is no evidence at all to confirm that government forces systematically massacred civilians in the operations zone or that the number of civilians killed even remotely approached the 733 or 926 victims variously cited in the press.

NARRATOR:

Greentree’s initial report was never released, and to this day he says he doesn’t know who changed his findings. The final draft, which Enders read from, described what happened as a military operation that resulted in civilian casualties.

The U.S. would continue funding the Salvadoran military.

Having averted the crisis, the Reagan administration went after the reporters for the Times and Washington Post who’d broken the El Mozote story. They had already been critical of how the press was covering America’s involvement in El Salvador.

ROGER FONTAINE, Reagan Latin America policy adviser:

It’s not just El Salvador. If we took The New York Times approach, I would guess that all of Central America, at least all of Central America, would be in the hands of governments which are manifestly unfriendly to the United States.

SUSAN MEISELAS:

Nobody believed Rufina. The denial, first to the State Department, and then the attacks, more on you than on me, for writing what they accused you to have written as leftist propaganda, communist propaganda, whatever.

RAYMOND BONNER:

The reaction was fury, vicious. They attacked us as reporters. The Wall Street Journal did a whole editorial damning me. A reporter out on a limb, and—no, I was not prepared for that.

The United States government was going to back the Salvadoran government come what may, and this was just another blip on the way to the support, so of course they were going to claim we were lying.

SUSAN MEISELAS:

It really wasn’t until the bones were exhumed that people believed.

NARRATOR:

For the next decade, the story of El Mozote receded as the civil war in El Salvador raged on.

Then, in January 1992, the government and the rebels reached a peace agreement. As part of the deal, both sides agreed to let the U.N. investigate alleged atrocities during the war. A U.N.-sponsored forensic team started digging in El Mozote.

MALE NEWSREADER:

In what used to be the local church they have now found more than 40 skeletons, nearly all children and infants.

MERCEDES DORETTI, Forensic anthropologist:

There’s also kids just like 3, 4, 5, 6 years old.

NARRATOR:

Mercedes Doretti was one of the forensic anthropologists at the site.

MERCEDES DORETTI:

As we start digging, we start finding children, one after the other one after the other one. It was an extremely difficult situation to see. You see all these little dresses. We will have to look at the pockets of the girls and little boys. And we found toys, all kinds of little things that kids will have. There were babies. The average age that was established was 6 years old.

And we found 263 cartridge cases inside the convent or immediately outside. The majority of the ammunition that was found there was coming from the U.S. government. All the evidence pointed to large-scale extrajudicial execution.

MALE NEWSREADER:

The forensic scientists say everything they have found is consistent with what human rights groups have said for years: that American-trained Salvadoran troops went on a four-day rampage, massacring 800 to 1,000 civilians while in search of leftist guerrillas.

RAYMOND BONNER:

That had a very big impact. Rufina Maya was there during that. She said, “Now we see the truth. Now we have the proof of what happened.”

MERCEDES DORETTI:

The exhumation of the convent attracted an enormous amount of international press, and seeing all these little skulls and little remains of all these kids, I think that the government wanted to stop that kind of images and that kind of news to come out.

NARRATOR:

A U.N. report would go on to accuse senior members of the Salvadoran military of human rights violations during the war, including at El Mozote.

Within days of the report, the Salvadoran Congress passed a sweeping law granting amnesty to anyone implicated in the atrocities.

CARLOS DADA, El Faro:

I was 21 years old. I wrote it down, the day they passed the amnesty law. And I wrote, “Here is our homeland dancing with the deaths of its own kids.” That was the amnesty law for me. A party made up over dead people. I still feel the same.

NARRATOR:

Carlos Dada founded the investigative news site El Faro. He and his colleagues kept pursuing the story, pushing for someone to be held accountable.

CARLOS DADA:

The fact that you pass an amnesty law or the fact that the official narrative is “let’s leave behind everything and move on” doesn’t take the victims anywhere. They are still there. There’s still thousands of mothers looking for their disappeared. There’s still thousands of people that feel they have not been served justice. But they still remember their killed children, their killed husbands, their killed neighbors.

What happened in El Mozote was the worst massacre post-World War II in all Latin America. That’s what happened at El Mozote. What happened after the massacre is the cover up of the massacre. I don’t think you can hide the killing of a thousand people. I just don’t think you can do that.

NARRATOR:

Over the following years, victims’ remains were returned to their families, and the government apologized, but there was little movement towards holding anyone accountable.

Then, in 2016, 35 years after El Mozote, the Supreme Court of El Salvador sided with human rights groups and victims’ lawyers and overturned the amnesty law.

CARLOS DADA:

The Supreme Court ruled that the amnesty law wasn’t constitutional, and this allowed for the opening of some of the cases that had been left into oblivion by the amnesty law. The first of those cases was El Mozote.

NARRATOR:

Ray Bonner, now working for Retro Report and ProPublica, returned to El Salvador to cover the developments.

RAYMOND BONNER:

The last time I was here, I walked in.

NARRATOR:

He visited the scene of the massacre, where people were streaming in to pray at a memorial that had been erected.

RAYMOND BONNER:

A hundred and forty of them children less than 12 years old.

Did you see them killed?

ELDERLY MAN:

[Speaking Spanish] Yes, my mother, my siblings, my wife, my children. It’s tough to see such things without being able to do anything about it.

NARRATOR:

Bonner tracked down a witness who was going testify in a preliminary hearing about the massacre.

Amadeo Martinez Sanchez was 8 years old when Salvadoran soldiers killed 24 of his relatives, including his mother and his siblings, the youngest only a year old.

AMADEO MARTINEZ SANCHEZ:

[Speaking Spanish] They died without knowing why they were brutally assassinated, starting with the children, who were angels. The feeling is always with you. You can’t pretend and try to be tough.

NARRATOR:

Days later, pretrial hearings were getting underway in the nearby town of San Francisco Gotera for more than a dozen former high-ranking military officers. Bonner joined El Faro journalist Nelson Rauda in the tiny courthouse.

NELSON RAUDA, El Faro:

We’re a country that maybe has some sort of amnesia with its history. There’s still people that say that in El Mozote what was going on was a fight between the guerrilla and the army, or that the amount of bodies in El Mozote is explained because it was a clandestine cemetery.

NARRATOR:

All the officers contested the charges against them, and the hearings would stretch on for several years.

JUAN BASTILLO:

[Speaking Spanish] Go ahead, take pictures. Take lots of pictures.

NARRATOR:

Then there was a breakthrough: former air force commander Gen. Juan Bastillo said in court that Salvadoran soldiers carried out the massacre.

NELSON RAUDA:

The trial is a landmark in our democracy. It might set a new page for El Salvador, and build upon from there, that killing 989 people, a majority of children, cannot go without punishment in our country.

NARRATOR:

After nearly five years of pretrial hearings, the judge in the case, Jorge Guzman, was on the verge of taking the case to trial. But the president of El Salvador had other plans.

PRESIDENT NAYIB BUKELE:

[Speaking Spanish] We must all begin to create the El Salvador that we want to see.

NARRATOR:

President Nayib Bukele has described himself as the world’s coolest dictator. He’s made Bitcoin an official currency of El Salvador, rallied the military behind him and pushed his country towards authoritarianism.

NELSON RAUDA:

The Bukele administration has gained control over everything that they can control, and the things that they cannot control, they attack.

NARRATOR:

In the summer of 2021, he effectively purged the judiciary, paving the way for allies to be appointed by his hand-picked Supreme Court. Among the casualties was Judge Guzman.

NAYIB BUKELE:

[Speaking Spanish] And now they come here to talk? To restore justice and historical memory?

NARRATOR:

Bukele had been critical of those who’d brought the El Mozote case.

NAYIB BUKELE:

[Speaking Spanish] They are scoundrels and they don’t care. They come to show their faces after 40 years and tell lies.

NARRATOR:

The president had even blocked Judge Guzman from accessing military records, despite a court order.

NELSON RAUDA:

The president attacked the judge, he attacked the victims, he attacked the organizations, he attacked the lawyers of the victims and he attacked the press. We are now at a state where Judge Guzman had brought the case to nearly the brink of having a decision, to a point where we don’t know if the case is going to continue, and if it continues, how it will continue.

NARRATOR:

The judge spoke to Rauda after leaving the case.

JORGE GUZMAN:

[Speaking Spanish] Even after 40 years of these events, and the other events that followed, we have not had the capacity to investigate them. A great danger in this country is that authoritarianism prevails and is allowed to govern our nation.

RAYMOND BONNER:

The current president of El Salvador does not want this case to go forward. The elite in that country, the ruling class in that country does not want accountability. It’s that simple. They didn’t want it in 1982, and they don’t want it today.

NARRATOR:

As for the United States, many Salvadorans say that it should be doing more to challenge Bukele’s actions, and given America’s history in their country, it should at least issue an apology.

NELSON RAUDA:

Imagine if you had 24 of your relatives killed and the U.S. government says nothing happened there. The U.S. kept backing up a government that were violating human rights because of a greater goal of stopping communism. And after it occurred, the U.S. government tried to cover up the massacre.

SUSAN MEISELAS:

Unfortunately, we don’t see the implications of much of what we do in the world. It’s always beyond our sight. Can the truth help Salvador outlive hate? This is the important thing.

NELSON RAUDA:

If you can’t have justice in the El Mozote trial, can you have justice in El Salvador? I think that the answer is clearly “no.”

AMADEO MARTINEZ SANCHEZ:

[Speaking Spanish] How many people have died seeking justice that never comes? Look, we as victims are going to keep demanding justice so that this historical memory is never forgotten. Because of this massacre that happened in El Mozote, we’re going to keep fighting forever, forging forward, because if we backtrack, we’ve lost.

WRITTEN AND PRODUCED BY Kit R. Roane

SENIOR PRODUCERS Frank Koughan Molly Knight Raskin

EDITORS Brian Truglio Sebastián Díaz

CAMERA Víctor Peña Neil Brandvold Liam Dalzell Aaron Tomlinson Cullen Golden Cory Dahn

SOUND Jack Norflus

ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS Katherine Wzorek Meral Agish Jessica Alvarenga

GRAPHICS Cullen Golden

FACT-CHECKING Angely Mercado

ONLINE EDITOR/COLORIST Jim Ferguson

SOUND MIX Jim Sullivan

ARCHIVAL PRODUCERS Sylvia Cahill Rebecca Losick

ARCHIVAL ASSOCIATE PRODUCERS Andrew Mayz Emily Orr Denise Cervantes

PRODUCTION MANAGERS Alex Mager Victor Couto

ASSISTANT EDITING Alex LaGore

MEDIA MANAGER Aaron Thomas

POST PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Ryan Brown

MUSIC John E. Low

ADDITIONAL TRANSLATION Daffodil Altan Jessica Alvarenga Tatiana Burgos-Espinal Juliana Torres

ARCHIVAL MATERIALS AFPTV Associated Press Neil Brandvold Monica Campos Vladimir Chicas El Faro F.I.L.M. Archives, Inc. Getty Alain Dejean / Getty Images Robert Nickelsberg / Getty Images Journeyman Susan Meiselas / Magnum Photos Glen Silber, Catalyst Media Productions Pond5 Screenocean/Reuters WPA Film Library Nelson Rauda Zablah

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS ABC The New York Times The Washington Post The Wall Street Journal CBS Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen

FOR PROPUBLICA

SENIOR EDITOR Kit Rachlis

PRESIDENT Robin Sparkman

MANAGING EDITOR Robin Fields

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Stephen Engelberg

FOR RETRO REPORT

HEAD OF STRATEGY AND PARTNERSHIPS Colleen McCarthy

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Kyra Darnton

FOUNDER Christopher Buck

Original funding for this program was provided by public television stations, Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Ford Foundation, Abrams Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Park Foundation, FRONTLINE Journalism Fund with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen and Laura DeBonis.

FOR FRONTLINE

DIRECTOR OF POST PRODUCTION Megan McGough Christian

SENIOR EDITOR Barry Clegg

EDITOR Brenna Verre

EDITOR Joey Mullin

ASSISTANT EDITOR Tim Meagher

PRODUCTION ASSISTANT Stevie Jones

FOR GBH OUTPOST EDITOR Deb Holland

SENIOR DIRECTOR OF PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGY Tim Mangini

INTERNS Ryan Everitt Sophia Gardner Sabrina Lee Raya Tarawneh Juliana Torres

FRONTLINE / EMMA BOWEN FELLOW Maya Chadda

SERIES MUSIC Mason Daring Martin Brody

EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT Will Farrell

OUTREACH SPECIALIST Joshua Rae

IMPACT PRODUCER Erika Howard

DIGITAL WRITER & AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIST Patrice Taddonio

AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT EDITOR Anahita Pardiwalla

DATA ANALYST Ben Abrams

ASSISTANT EDITOR, DIGITAL Tessa Maguire

SERIES PUBLICITY MANAGER Anne Husted

ARCHIVES & RIGHTS MANAGER John Campopiano

FOR GBH LEGAL Eric Brass Jay Fialkov Janice Flood

SENIOR CONTRACTS MANAGER Gianna DeGiulio

BUSINESS MANAGER Sue Tufts

BUSINESS DIRECTOR Mary Sullivan

SENIOR DEVELOPER Anthony DeLorenzo

LEAD DESIGNER FOR DIGITAL Dan Nolan

FRONTLINE/COLUMBIA JOURNALISM SCHOOL FELLOWSHIP

TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW Taylor Eldridge

ABRAMS JOURNALISM FELLOW Aasma Mojiz

FRONTLINE/NEWMARK JOURNALISM SCHOOL AT CUNY FELLOWSHIPS TOW JOURNALISM FELLOW Paula Moura

FRONTLINE/FIRELIGHT INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALISM FELLOWS Cristina Ibarra Ursula Liang

EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Lauren Prestileo Callie T. Wiser

DIGITAL PRODUCER/EDITOR Miles Alvord

HOLLYHOCK FILMMAKERS IN RESIDENCE Abby Ellis Marcia Robiou

SERIES PRODUCER AND EDITOR Michelle Mizner

INVESTIGATIVE PRODUCER Daffodil J. Altan

DEPUTY DIGITAL EDITOR Priyanka Boghani

DIGITAL EDITOR Jennifer Wehunt

EDITORIAL COORDINATING PRODUCER Katherine Griwert

POST COORDINATING PRODUCER Robin Parmelee

SENIOR EDITOR AT LARGE Louis Wiley Jr.

FOUNDER, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER AT LARGE David Fanning

SPECIAL COUNSEL Dale Cohen

SPECIAL PROJECTS EDITOR Philip Bennett

DIRECTOR OF AUDIENCE DEVELOPMENT Maria Diokno

SENIOR PRODUCER FOR SPECIAL PROJECTS & INNOVATION Carla Borrás

SENIOR PRODUCERS Dan Edge Frank Koughan

SENIOR EDITOR Lauren Ezell Kinlaw

SERIES SENIOR EDITOR Sarah Childress

MANAGING DIRECTOR Janice Hui

MANAGING DIRECTOR Jim Bracciale

MANAGING EDITOR Andrew Metz

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Raney Aronson-Rath

A FRONTLINE production with Retro Report © 2021 WGBH Educational Foundation and Retro Report, Inc.

FRONTLINE is a production of GBH which is solely responsible for its content.

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.