Dispatch

Behind ‘South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning’

September 27, 2024

Share

Listen & subscribe

In the decades after the Korean war, around 200,000 children born in South Korea were adopted by families in Western countries. As adults, some of those adoptees have returned to South Korea to learn about their origins — only to discover that what they had been told wasn’t true.

A new documentary from FRONTLINE and The Associated Press, South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning, details the stories of adoptees and birth parents searching for answers, charts the history of foreign adoption out of South Korea, investigates allegations of wrongdoing including falsified papers and switched identities, and reveals the forces that helped to drive an unprecedented international adoption boom.

Together with director Lora Moftah, AP reporters Kim Tong-hyung and Claire Galofaro join The FRONTLINE Dispatch to talk about their investigation.

“Korea constantly tailored its policies and laws to meet the child demands of the West, while it was also trying to reduce the number of mouths to feed,” Kim says. “I think our reporting and the FRONTLINE documentary established that dynamic of supply and demand in a deeper way than the previous reports on the subject.”

Stream South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning on FRONTLINE’s website, FRONTLINE’s YouTube channel, or the PBS App. Read and listen to more accounts from Korean adoptees in the interactive story, “Who Am I, Then?: Stories from South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning.”

Want to be notified every time a new podcast episode drops? Sign up for The FRONTLINE Dispatch newsletter.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Since the 1950s Around 200, 000 children from South Korea have been adopted by families in other countries.

FANNY THIEBAULT: I was adopted into France in 1982.

ANNA SAMUELSSON: I was adopted—

LISA NYSTROM: I was adopted—

THERESE OERTENBLAD: I was adopted to Sweden in 1982.

MULTIPLE ADOPTEES [in unison]: I was adopted to the United States.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: As adults, many adoptees have returned to South Korea in hopes of meeting their birth parents and learning about their origins. But many have left with more questions than answers, and some have learned that they were not at all who they were told.

AMB. SUSAN JACOBS, Special Advisor for Children’s Issues, 2010-17: There were a lot of children brought to the States who might not have been orphans.

ROBERT CALABRETTA: What do you do when you find out your origin story is marked with grievous injustice?

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Reporters from the Associated Press have been investigating allegations of wrongdoing in South Korea’s adoption system.

KIM TONG-HYUNG: This is a summary of a meeting between the government and the head of the adoption agencies.

CLAIRE GALOFARO: Do you know when this meeting was?

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: South Korea’s adoption reckoning, and is a new documentary from Frontline and the Associated Press. The team behind the film joins me today, reporters Tong-hyung Kim and Claire Galofaro from the Associated Press, and director Laura Moftah. I’m Raney Aronson-Rath, editor in chief and executive producer of Frontline, and this is the Frontline Dispatch.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Tong-hyung, Claire and Lora, thanks so much for being on the Dispatch.

LORA MOFTAH: Thanks for having us.

TONG-HYUNG KIM: Yeah. Thank you for having us.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: So Tong-hyung, of course, I have to start with you. Can you just tell us how you got interested in adoptions in South Korea in the first place?

TONG-HYUNG KIM: I really didn’t have a[n] awareness about these deeper problems surrounding Korean adoptions for really most of my life. Uh, I began, developing a reporting interest in adoptions about, uh, nine years ago. I was then working on an investigative story, surrounding the abuse at a facility called Brothers’ Home. It was where thousands of adults and children deemed as vagrants were uh grabbed off the streets and confined in a huge, compound where they were subject to slave labor and exposed to extreme violence, uh during South Korea’s military rule and as I was interviewing inmates from this facility, I found that a lot of inmates said they understood that the youngest inmates of this facility, uh, children under the ages of three or five or even infants, were being constantly adopted abroad. Even without, deep understanding of the Korean adoption system then, the possibility that children from this facility called Brothers’ Home being adopted abroad really kind of blew my mind. So, I started to work on a separate story. And confirming, adoptions from Brothers’ Home required me to just find every government archive and file I could, you know, find, read, track every statistic, uh, meet whoever is gonna meet me, like former adoption workers, or former officials of Brothers’ Home, or policy makers, and during that process I developed, uh, a more deeper understanding of the adoption system. So that’s how I got started.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Claire, tell me about the first time, you know, your editor called you and told you about this story and what happened next.

CLAIRE GALOFARO: Coincidentally, I had been working on a project um where it involved international adoption. It was about this US Marine who adopted an Afghan war orphan, but sort of skipped all of the traditional processes of international adoption. And so to report that story, I’d kind of, sort of done some reporting on international adoption and become really interested in it. Um, I think that was really just a coincidence, but, I did find it to be a topic that was sort of so rich and so compelling. You know, these are, you know, people’s lives, baby’s lives that are being decided by adults. And I just found that to be a really compelling reporting avenue. Tong-hyung and I had actually gotten to work together when I was at the Olympics in South Korea in 2018. So, we had some familiarity with each other and um Tong-hyung had been working on this for years and had done this really incredible reporting and as they reached the, the end, the sort of the final months of the reporting, they wanted somebody to be able to help kind of connect the dots with the Western side, the Western governments and particularly the United States.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Lora, you got involved because we wanted you to make a film with us this year, and, you know, one of the things that we have the privilege of doing with the AP is really translating investigative journalism into film. What was the first thing when you heard about this that you thought you could land in the form that we produce in, which is documentary?

LORA MOFTAH: Yeah, I mean, I have to say when I was sent over the materials for this investigation. I was startled. I mean, I’ve of course seen stories about incidents and issues and international adoption over the years, but what happened in Korea, as Tong-hyung found in his investigation, that was all new to me. So I began reading through his reporting. andI think what made this so captivating to me as a filmmaker was that there was this real human core to this story, like every single adoptee we spoke to and we spoke to many, many more than were actually in the documentary, they all just had these extraordinary stories full of twists and turns and just jaw dropping revelations. Um, and many of them were still in this ongoing process of questioning and discovery. So that’s really where we started when we began thinking about developing this investigation into a documentary.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Tong-hyung, take a moment and help us understand what are the major takeaways from the investigation, and in general, what patterns did you see emerge?

TONG-HYUNG KIM: Well, I think, like, the major takeaways is like, you know, we detailed how widespread the fraudulent practices of, how agencies gather children, how they created paperwork to, describe most of the children as abandoned orphans who are eligible for adoptions in the United States, although, you know, other evidence from government records and files, including, documents that show where the agencies were getting their children from suggest that most of the children sent, abroad during the peak of adoptions in the 80s would have had known parents. And I think we also detailed the demand side of things – how this huge demand for children from the West also pushed Korea to just maintain that supply of children for so many years.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: So, right. Tong-hyung, one of the things that’s been so interesting about how the adoption story has changed is how it’s changed inside South Korea as well. Tell us about what’s happening in South Korea right now, and the response of the government was to your reporting.

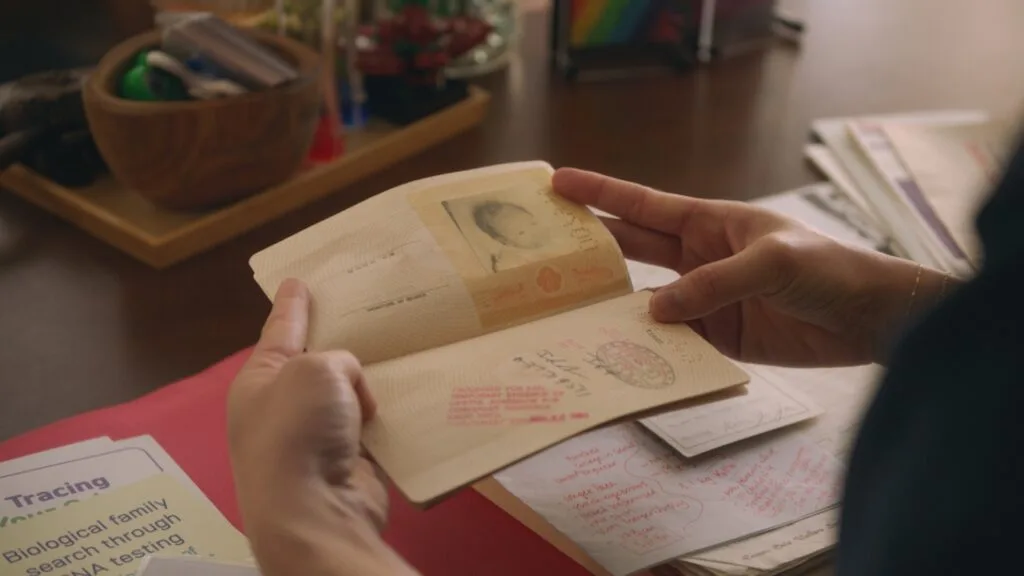

TONG-HYUNG KIM: Well, many Korean adoptees, thousands of them, have returned to Korea in recent years in search of their identities, uh, trying to attempt to reconnect with their biological families. And they have been surprised to discover that for so many of them, the child origins described in their paperworks turn out to be inaccurate or in some cases, downright falsified. And South Korea is currently has a fact finding commission that is investigating human rights issues under the military governments that ruled the countries from the sixties to eighties. Now adoptions is part of that investigation. Uh, the commission is investigating the cases of more than 360 adoptees who believe that their adoptions were facilitated by manipulated child origins. So it’s becoming more difficult for the government to avoid questions about how the adoption system was built. And right now, Korea is promising reforms with the sight set on the future, like preventing future abuses and also strengthening the government responsibility and control over the whole adoption process, but at the same time, uh, policymakers are at a loss at what to do with these mountains of inaccurate or falsified records that have been accumulated over the years. And if the fact finding commission finds the government at fault for all these often unnecessary child-parent separations that could lead to significant consequences because a lot of adoptees are hoping to use the commission’s investigation results as grounds to pursue possible, you know, damage suits against their government or other agencies.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Lora, let’s talk about some of the people we feature in the documentary. Tell us about your opening character and how you meet them and, and just set the scene for us.

LORA MOFTAH: So our opening is actually not with an adoptee, but with a mother. Um, this is a Korean woman, who had her child go missing in the mid 1970s. And she spent the last decades searching for him. You know, she went to every police station. She even went to adoption agencies asking, have you seen my son? He’d sort of run outside to play with his friends on the street and just never came back. Um, so it was this missing child case and years later she decides to submit her DNA to a database, which is actually, you know, something that I understand isn’t sort of the most widely done thing in Korea. It’s not like in the U.S. where you know, everyone’s doing an ancestry DNA thing. Um, so she does this just sort of one last Hail Mary effort and lo and behold, there’s a match. Um, she is reconnected with her son and she discovers that he’s actually been adopted to Norway. He was adopted to Norway shortly after he went missing despite all the various notices and notifications she made of various agencies, police, um, et cetera, and yet he was adopted out of the country. How could this have possibly happened? It’s just, you know– I don’t speak Korean. Um, I was present for her interview, and even though I didn’t understand a word as she was saying it, um, I knew exactly what she was saying. You could see the pain etched in her face in, you know, the waiver of her voice. It was a completely devastating story. And I think so, uh, I won’t say it was emblematic of this program because of course, you know, there were many adoptions that were completely legitimate. They were done for good reason. And, um, many adoptees have had you know, good, happy adoptions. But this was a case that I think helped us to understand just how this could go so very wrong. The lack of accountability and guardrails on this thing and the sort of voracious campaign to send kids out at volume as quickly as possible. So uh, we decided to start our film with her story because while it might not be representative of the, you know, 200, 000 plus, um, children that were adopted, it was kind of representative of what this investigation found,

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Right. And so, Tong-hyung, you actually sat with the mother, Chae Young Ja, and it was one of the most emotional interviews you’re sitting with a mother who lost her child and tell us about her journey to find him and then finding him.

TONG-HYUNG KIM: Well, when I talked with her, her pain was still fresh. She just vividly talked to me about the day he disappeared, and when I first went to her motel where she lives, you know, the first, one of the first things that comes to your eyes, this huge stack of green missing child posters she had. And, you know, like her reunion with her son was a very happy moment for her, but also, also sad in a way because she believes she lost the past 50 years, an opportunity to spend with him. She’s obviously very happy that she found her son. She says she’s one of the luckier parents because she described that experience as, you know, fetching a star from the sky, but at the same time, her son now speaks a different language. He has his own established life in a country that’s far away. And so there’s also this pain about the lost opportunity to raise her own son. And when I talked with her, she was very eager to pursue accountability for the, uh, of the Korean government and also the adoption agency Holt. She always says her heart trembles because she was this close to just, never ever meeting her son again.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Seeing her and having her tell the story is like one of the most memorable parts of the film. As a mother, you know, it’s just imagining that as well. You know, both sides of that are just devastating.

CLAIRE GALOFARO: Yeah and I just wanted to just add something really quickly to what Tong-hyung and Lora were talking about…

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: No, no, yeah, please.

CLAIRE GALOFARO: A lot of the adoptees we’ve talked to have said that,something in their life spurred them to want to find their origin. A lot of them said it was having children of their own and for the first time seeing somebody who is biologically related to them. And they had, because so many people were documented as abandoned, they did this sort of systemically, they had kind of come to terms with that throughout their life. Like, I was abandoned. And that’s just the way it was and then they find out that that wasn’t true and that is a pretty, um, obviously monumental realization and they have to grapple with it all over again, like I wasn’t abandoned, I was wanted.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Right. Right.

CLAIRE GALOFARO: Um, and I think that’s been a pretty, I mean, it’s been pretty startling to me to have those conversations with adoptees about, you know, what it’s like to make peace with being abandoned the first time around and then have to make peace with having not been abandoned later.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Right. And you’re, you’re really looking at their faces in the film and they’re telling you these stories and it’s really profound for every single one of them, So Claire, I was hoping you could also tell us your perspective on this. What did you feel the major takeaways were?

CLAIRE GALOFARO: So yeah, I think that my, I think the most, um, notable takeaways for me are that, all these people on the ground saw what was happening, that people who were running, humanitarian organization said, you know, something really wrong is happening here. Um, and in addition to that, you know, we found documentation where a very well respected international child welfare organization called International Social Service was in real time, documenting their concerns with adoption agencies competing for babies. Um, they wrote that they’d heard, um, and had evidence that, that they were, bribing and pressuring mothers. Um, they described how Western governments were processing these adoptions like an assembly line — that’s a quote from one of their reports —um, that they described it as a callous way that these children were leaving Korea and going to the West. That they were just, that their adoptions were just being rubber stamped, and that Western countries weren’t doing enough to ensure that these kids were truly orphans and that they were going to good Western homes. And we also found sort of, um, even more, I think, important than, than this sort of overall sort of rubber stamping of visas, Tong-hyung found documents from the 1970s where some Western diplomats and governments were actually pressuring Koreans to keep the baby pipeline going. Korea had tried to shut down adoptions to some Scandinavian countries because, um, North Korea had been using their adoption program to sort of embarrass the South as a sort of political cudgel to say, you know, South Korea is selling off Korean children. Um, so South Korea tried to shut down adoptions to some countries where that message was sort of taking hold. And diplomats from those countries came to the Korean government and were like begging for babies, you know, in some ways threatening the diplomatic relationships between those countries. And, and. Korea, under that pressure, reversed course and decided to continue sending babies to those countries.

TONG-HYUNG KIM: Yeah. And from the Korea side, it was obvious that, you know, South Korea continued to target the children of its weakest citizens. Uh, so, like, [00:20:00] In the fifties, it started out as, the birac ial, uh, children of Korean, Korean women and American soldiers who were shunned from the conservative society. Then, adoptions were fully Korean children, uh, newborns of unwed mothers or, you know, children from poor families or just any parent who, for whatever reason, was having difficulties raising their own children. So Korea constantly, uh, tailored its policies and laws to meet the child demands of the West, while it was also trying to reduce the number of mouths to feed by removing the children it didn’t see as worthy future citizens. So, I think our reporting, uh, detailed this, uh, alignment of interest, from you know, Korea, which wanted less babies, and the United States and the West, which wanted more children for their domestic families, and I think that really differentiates our reporting from the previous reporting, which, you know, usually focused on private adoption agencies. I think our reporting and the FRONTLINE documentary established that dynamic of supply and demand in a deeper way than the previous reports on the subject.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Robyn Park and Michaela Dietz are two American women who you feature in the film, and they were both adopted from South Korea in the 1980s. Can you tell us what happened when they went searching for their birth parents?

LORA MOFTAH: Yeah, Robyn and Michaela are sort of cases of what we’ve been calling switched cases, which is essentially, um, South Korean adoptees who return to South Korea, go back to their adoption agencies looking to be reunited with their biological families. Um, both Robyn and Michaela went there, found their paperwork, were reunited with these families that they were told, you know, these are your families. Um, and both of them for different reasons later then did DNA tests and discovered that these families they’ve been told were their biological families were actually not related to them, um which was a tremendous shock to both of them. Both of them then sort of proceeded on journeys to find out why they asked their adoption agency, Eastern, how could this have happened? And the prevailing theory is that they were essentially switched or their documents were switched. So, for whatever reason, they had an initial set of documents and then they were swapped out with another baby, their, their identity, their paperwork, um, and sent to the United States or other countries with this incorrect paperwork, incorrectly identifying their birth families. So, uh, Robyn and Michaela’s stories, though, took, I think, different trajectories. Both of them continue to look for their families. Robyn has not been successful. Whereas Michaela, through sort of a serendipitous turn of events, and she’s actually the only adoptee who’s a switched case, um, that we’re aware of this happening with, she did find her biological family. It’s just a process that is so fraught emotionally because you’re talking about these really big weighty issues for adoptees, their origins, their identity. So, you know, it’s sad that, Robyn has still not been able to find her family, but in Michaela’s case even though she did get, you know, the happy ending, um, it’s no less emotionally fraught and that’s one thing we’ve heard consistently speaking with adoptees in the course of this project.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Right. And what are the adoption agencies that you all featured in the film saying about this?

TONG-HYUNG KIM: Yeah, Eastern did not specifically comment on individual cases like Robyn’s, But I was able to reach their president, and while she did not comment on specific cases as well, she defended the agency’s overall policies. She said it was about, uh, finding foreign homes for children she described as discarded and she was very proud of the agency’s legacies. She did admit that, uh, some adoptions could have gone wrong, but she described them as mistakes that inevitably happened because so many kids had to be adopted abroad to foreign homes and, you know, mistakes would happen in such a large process. Uh, Holt Children’s Services, which is the largest agency that handled about half the adoptions out of Korea, they also did not, uh, comment on specific cases when we reached them. Uh, their president or their head uh adoption official did not respond to my calls and texts either. But Holt, in recent public comments, have been denying systemic problems about their practices, and they have described the adoptee complaints as based on misunderstandings. So, in a similar way to Eastern, they have been defending their practices as a way to find good Western homes for needy children.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Claire, tell me about the conversation that you and Tong-hyung had with Holt International?

CLAIRE GALOFARO: We spent several hours with Susan Cox, who was a longtime executive at Holt International, um, at their headquarters in Eugene, Oregon, and they’re really proud of their legacy. You know, they have essentially a museum in the lobby of their headquarters um that sort of tells the origin story of international adoption, which was really created for by Holt right after the Korean War in the 1950s. Um, and they maintain that their intention never wavered, that they remained committed all of those years to finding homes for the neediest children, that Korea could not care for its own children at that time, and they needed to be sent abroad to give them good homes. You know, one of the things we were looking at specifically was, you know, it felt like, it felt to us, and I think to many of the people we interviewed for this project, that it was sort of a paradox that, you know, Korea was really struggling in the 1950s right after the war, but then over the next decades it emerged, you know, really as an economic superpower. It was planning to host the Olympics in 1988 as its sort of coming out party. Um, it had really ascended on the global stage, but still at the same time, the number of adoptions were skyrocketing. They peaked in the 1970s and 1980s, um, eventually nearing almost 9,000 adoptions a year in the mid 1980s, just as Korea was emerging as this really, um, as this force on the world economic stage. Um, and so, you know, that was one of the things we were trying to make sense of. What Susan Cox with Holt said was that, you know, there were still a lot of scars of war that, from her point of view, um, that there were still a huge number of children that couldn’t be cared for in Korea. That if they weren’t sent abroad, they would, they would have grown up and lived their lives in orphanages and other facilities, um, and that Holt’s mission was to find them good homes. And she absolutely rejected the allegation that Holt and other agencies were sort of foraging around Korea for babies. She, um, you know, insisted that, that’s not what was happening, that they were, you know, committed to taking care of the weakest citizens.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: And Claire, what was the government response? Like what was the accountability response?

CLAIRE GALOFARO: You know, I talked with the State Department several times over the course of the months that I was working on this. And, they wanted to emphasize that adoption today is very different than it was in the 1970s and eighties. The United States ratified what is known as the Hague Convention. It is a sort of international agreement that says this is how intercountry adoption should work. Um and since then, the number of adoptees to the United States has plummeted. The State Department points to that to say, you know, there are far higher standards today. There are much stricter safeguards. Adoption agencies have to be accredited, and the accreditation process is, um, intense and tries to ensure that adoption agencies are acting ethically. And so, you know, their emphasis in the beginning of our conversations is that, you know, they want to focus on the future. They want to focus on ensuring that adoptions are done right today. Although, they did say, you know, fairly recently that our questions sort of compelled them to try to piece together their history from their archives. They said that they were working with an internal archivist to try to find documents and, you know, diplomatic cables related to adoptions in Korea during the time period we were looking at, which is the 1970s and 80s, when the number of children coming out of Korea peaked. Um, and so they said that it’s possible that children were sent for adoption with falsified or untrue paperwork. But they did emphasize that they have found no indication that U.S. officials were aware of that.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Claire, I was hoping you could help us understand the scale of the problem, um, in this system. And then do we have any idea of how many adoptees have run into problems tracing their birth parents?

CLAIRE GALOFARO: You know, that’s a question that we have contemplated so much throughout the course of this reporting, and I think we’ve sort of arrived on the answer that it’s really impossible to know. And that is simply sort of by the nature of how the system was built and designed. You know, for most people, it really takes reconnecting with their birth families to be able to know whether or not the story and their adoption paperwork was true. Um, but because there are so many obstacles for these people to actually do that, to be able to reconnect with their birth families, a tiny fraction of the people who go to Korea in search for that history actually find it, um, which is, you know, an incredibly frustrating and heartbreaking ordeal for them. But I think it also means that it’s really impossible to quantify how many adoptions were problematic because the adoptees themselves have been really unable to learn their true story.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Mm. Right. And I think that’s at the heart of this. Lora, as you were thinking about structuring the film, how did you think about what the most important thing that our audiences would take away would be? What were you hoping for?

LORA MOFTAH: Well, in terms of structure, we really used a kind of historical narrative as our, as our narrative spine. and we wove the, the, investigative process with that historical narrative and then embedded within that were these, these stories, these adoptee stories, the story of a mother of an adoptee that really anchor it, um, in this lived reality, which is distinct for every adoptee, but ultimately is about systemic issues, policies that were made by, people high above them and which had these irrevocable consequences, for these various adoptees.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: Claire, Tong-hyung, and Lora, thank you so much for joining me on The Dispatch.

LORA MOFTAH: Thanks for having us.

TONG-HYUNG KIM: Yeah, thanks for having us. Thanks for having us.

RANEY ARONSON-RATH: You can watch South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning on Frontline.org, Frontline’s YouTube channel, and the PBS app. And you can read and listen to more stories from the adoptees on our website too. We’ll share a link to our interactive story wherever you’re listening to this podcast.

Sign up for FRONTLINE Dispatch Newsletter

Related Documentary

South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning

FRONTLINE and The Associated Press examine allegations of fraud and abuse in South Korea’s historic foreign adoption boom

Related Stories

South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning

The FRONTLINE Dispatch

Related Stories

South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning

The FRONTLINE Dispatch

Explore

Policies

Teacher Center

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, with major support from Ford Foundation. Additional funding is provided the Abrams Foundation, Park Foundation, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, and the FRONTLINE Trust, with major support from Jon and Jo Ann Hagler on behalf of the Jon L. Hagler Foundation, and additional support from Koo and Patricia Yuen. FRONTLINE is a registered trademark of WGBH Educational Foundation. Web Site Copyright ©1995-2025 WGBH Educational Foundation. PBS is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization.